Women’s Work: Print, Manuscript, and the Receipt Book Genre

“Women’s work” is often deemed the work of the domestic space, the cooking, the cleaning, the day-to-day mindless minutiae required of the woman of the home. There is nothing particularly intellectual on the surface of this work, and the early modern texts that preserve the conventions of this labor (recipe books, household manuals and the like) are not those that make up the conventional literary canon. But there is more to this genre that meets the eye. Early modern women were indeed in charge of the household, and that meant all aspects of the household. They were in charge of feeding, nursing, maintaining and caring for all members of their households. The written works they used as references and guides circulated in the form of both printed books and handwritten manuscripts. Through these texts we can begin to reconstruct the actions, relationships, and rich intellectual lives of the women who used them.

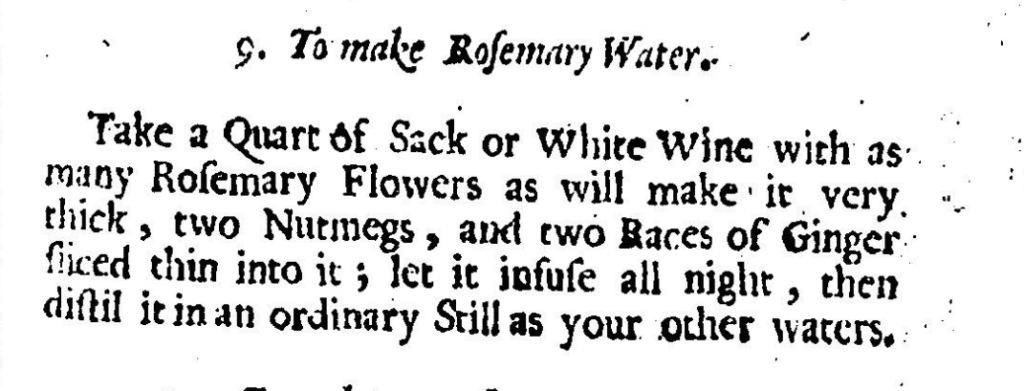

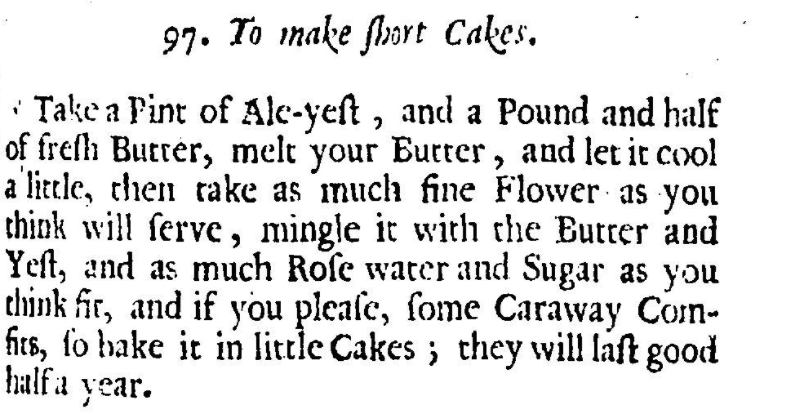

Print recipe books share some common conventions of the genre that an early modern reader might be on the lookout for as they perused the book shops and stalls that surrounded St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Like many genres, their front pages might be accompanied by an illustration, perhaps of a kitchen or a cook in action. These frontispieces helped to sell the book by showing its recipes in action. Recipe books would also be organized by theme, separating sweet desserts from soups and savory pies. The recipes would look different from our ideas of modern cookbooks. Most would not begin with a list of precisely measured ingredients and recommended equipment. Instead they would read in a more narrative way, instructing the reader and introducing new ingredients and actions as they went. Many recipes assumed a certain level of knowledge and expertise of their reader, that they were relatively experienced or at least aware of the actions that would take place in the kitchen. For instance, Hannah Woolley’s The Queen-like Closet includes a recipe for rosemary water that concludes: “Still as you would your other waters” (5). There are other recipes for waters in the book, but the author still assumes that the reader would have at least some rudimentary knowledge of how to make cordial waters. Ingredients were also predicated on some prior knowledge as well, as exact amounts were not always given. Another recipe in Woolley’s Queen-like Closet, for short cakes, advises the reader to use “as much fine Flower you think will serve” (47). Baking is not the precise science we view it as today, but based on the individual’s experience. Recipes are a site of experimentation in the early modern period, even as recipe books are bought for their instructional value.

Reading manuscript receipt books can be a completely different experience from reading those that have been published in print. There are no elaborately printed frontispieces, no long titles with detailed descriptions to sell their wares, and no prestigious names attached to the front page. However, despite their humble appearances, these books could be as essential to the running of an early modern household as their printed counterparts, and for researchers they are a rich reference for the study of women’s writing practices. Like print books, manuscript receipt books are not always devoted to only one kind of recipe. Culinary recipes are often combined with medical receipts, cosmetic receipts, and household recipes for concoctions such as ink. The culinary, medical, and cosmetic were intertwined in the early modern period, and our modern distinctions may not have been so clear cut at the time these receipts were written. Each genre of recipe would have been important to the smooth running of an early modern home.

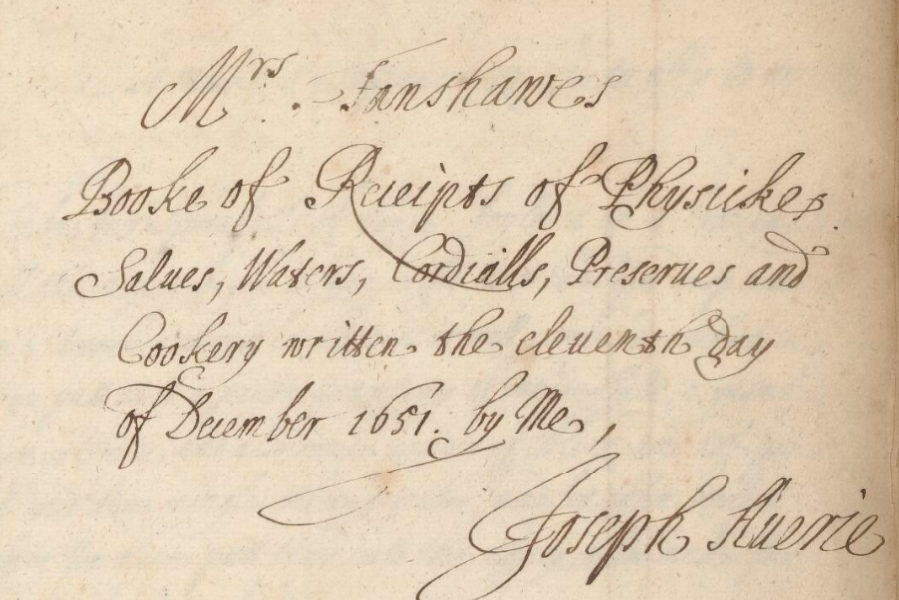

Manuscript receipt books, despite their aesthetic differences, do share many attributes with printed cookbooks. They have imposed organizational structures, often in the form of indexes or tables of contents, or sections devoted to particular kinds of recipes. The pages were often numbered by the compiler, and sections were blocked to provide adequate space to add more recipes in the future. Some of the conventions of literary manuscript culture also apply to receipt books, like provenance. Knowing the prior owner of a receipt book does not mean that the entire manuscript was written by them. Just as scribal copies of literary works and miscellanies commonly circulated, so did scribal and presentation copies of recipe books. Ann Fanshawe’s receipt book is a particularly famous example of this, as the scribe who wrote many of the recipes left his own inscription on one of the leaves. Multiple hands are often identified as owners over the years added recipes in their own hands. These receipt books also did not often come pre-bound. Instead loose sheets of paper could be gathered together, and pages could be inserted before they were finally all sewn together to make a complete book. It is common to see errors in pagination in receipt book when pages were numbered incorrectly or sewn together out of order.

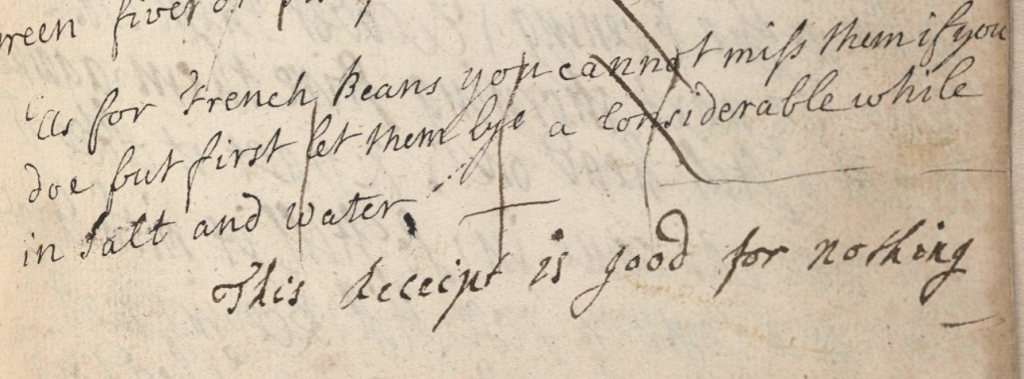

Many of these manuscript receipt books also show some evidence of use for some of the recipes in them. Often the Latin phrase ‘probatum est’ or ‘proved’ would be written in the margin for receipts that had been tried and successful. In other cases, recipes were not so well received. Receipt books show evidence of items being crossed out, adjusted, critiqued, or even dismissed entirely. Lettice Pudsey famously marked through one of the receipts in her book and annotated it, “This receipt is good for nothing” (56r). Not just static objects used as status symbols, these books were indeed in use in kitchens and homes (with varying levels of success).

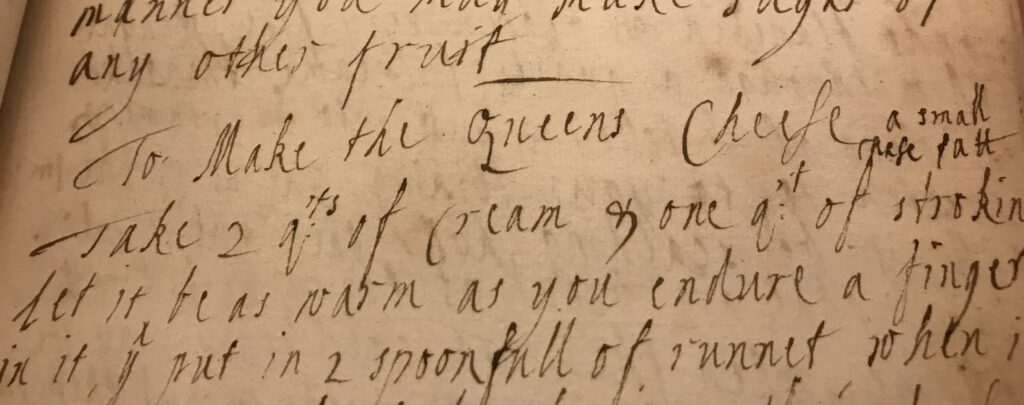

Attributions are some of the most valuable elements of the manuscript receipt book genre. Some recipes are noted by their authors to be from particular sources, sometimes from family members, physicians, friends, or even from the nobility. There are certain tricks to reading these attributions however, and often these notations cannot be taken at face value. A recipe attributed to the Queen may not have come from her personal collection. In fact, in all likelihood, she has no idea that this recipe exists! An attribution to a person of higher social standing could be a measure taken by the compiler to add prestige to their collection. But other attributions can be significantly more interesting, and they can be used to trace social and family networks of the authors. Family doctors might have been consulted for medical receipts, and other women in the family are common sources for receipts. Mothers and grandmothers would pass their useful recipes down the female line.

Outside of gleaning information about the social network of these receipt book owners, we can also better understand women’s relationships to print works through their manuscripts. Often, recipes from print recipe books ended up copied into manuscript books as these texts circulated alongside each other. Sometimes these recipes are attributed to their original print authors, but just as often they are copied in without attribution to the source. It takes keen research to find these receipts, but when they are found it is exciting evidence of what print books women were interacting with at the time. Sometimes this process would be reversed and manuscript receipts would end up in print. Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent had her own receipt book that seems to have served as a source for the book later published under her name, A Choice Manuall. These two modes of production were fluid and constantly informing each other.

Many extant manuscript collections of recipes pre-date the print works in our database authored by women. This tradition of women’s writing in the household was long-standing even before they were in print. Reading these two modes alongside each other can show how women, stereotypically confined to their households in the modern mind, were actually part of vibrant social, literary, and intellectual networks in which they were authors, inventors, and innovators. They are rich sources of information about how women worked, thought, communicated, and experimented in their homes and with each other. There are many questions we can continue to ask of these books as we pursue better knowledge about caregiving. These texts can help us redefine “women’s work” in the early modern period.

Works Consulted and Recommended Reading

DiMeo, Michelle and Sara Pennell ed. Reading and Writing Recipe Books, 1550-1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013. Print.

Leong, Elaine. “Collecting Knowledge for the Family: Recipes, Gender and Practical Knowledge in the Early Modern English Household.” Centaurus 55.2 (May 2013): 81-103.

Pennell, Sara. “Perfecting Practice? Women, Manuscript Recipes and Knowledge in Early Modern England.” Early Modern Women’s Manuscript Writing: Selected Papers from the Trinity/Trent Colloquium Ed. Victoria E. Burke and Jonathan Gibson. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. 237-55. Print.

Wall, Wendy. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016. Print.